From Hero to Zero with Learning Management Systems

Why and How LMSs fail in distributing knowledge

Abstract: Learning Management Systems provide more restrictions than access to educational resources and developing courses with the offered authoring tools is more tedious and intimidating task than a creative one. These claims are proved by adopting metrics from software-development, additionally a possible solution is presented: LiaScript is a domain-specific language that is based on Markdown and open-source principles, targeting interactive online-course development.

Keywords: LiaScript, LMS, MOOC, Software-Metrics, OER

Authors: André Dietrich & Sebastian Zug

1 Introduction

Learning Management Systems, so called LMSs, gain more and more popularity, especially in university education. Although these are mostly systems developed under an open-source license, they are commonly applied to restrict the access to educational resources. Cynically one could say, they are simply a continuation of locked up lecturer halls, brought to the internet. But even more than that, the integrated authoring tools offered by these LMS actually restrict the creation of online-course through unnecessary complex Graphical User Interfaces (GUIs), with lots of plugins, options, descriptions and repetitive click-events. Additionally, a course created with one system cannot easily be shared, translated, adapted by other authors, or simply reusing parts or apply versioning is not possible.

To prove these claims, we apply metrics from software- and GUI-development to measure the intricateness of the most widely applied systems. Furthermore, we show how most common problems in online-course development can be avoided, with a simple shift in mindset.

… instead of forcing humans to create courses by typing and clicking onto an endless set of opaque GUI elements, that can be easily interpreted and rendered by a machine … we should enable humans to express their thoughts and ideas with a simple and more natural language …

… that is why LiaScript was created …

2 Lineup of Different Ideologies

This comparison is focused on the creation and dissemination of educational content only. However, most LMSs also offer many sophisticated features on communication, management, assessment, or user analytics, see therefor [Ca14, Le05, Ma08].

2.1 LiaScript: Domain Specific Language (DSL) for Open-courSe Development

LiaScript [Di19] was born out of the idea to let anybody (even without programming skills) develop high-quality online-courses, with focus on content and the latest web-technologies. It was founded on open-source principles, simplicity, and (re)usability. The figure below shows some features of LiaScript:

A course is text-file written in Markdown [MD19], a lightweight markup language with plain text formatting syntax, designed for readability. Courses can be hosted as opensource projects on GitHub[1], together with required multimedia content, JavaScript libraries, and any other data. Code-blocks (line 46) can be made executable by attaching a JavaScript script-tag that defines how the source-code should be processed. To ease this step, we provide macros (line 54) that get replaced by HTML, JavaScript, CSS-annotations, Markdown, etc. Such macros can be parameterized and are evaluated by an internal text-substitution system at compile time. Additionally, it is also possible to import macros from other courses, which reduces boilerplate code.

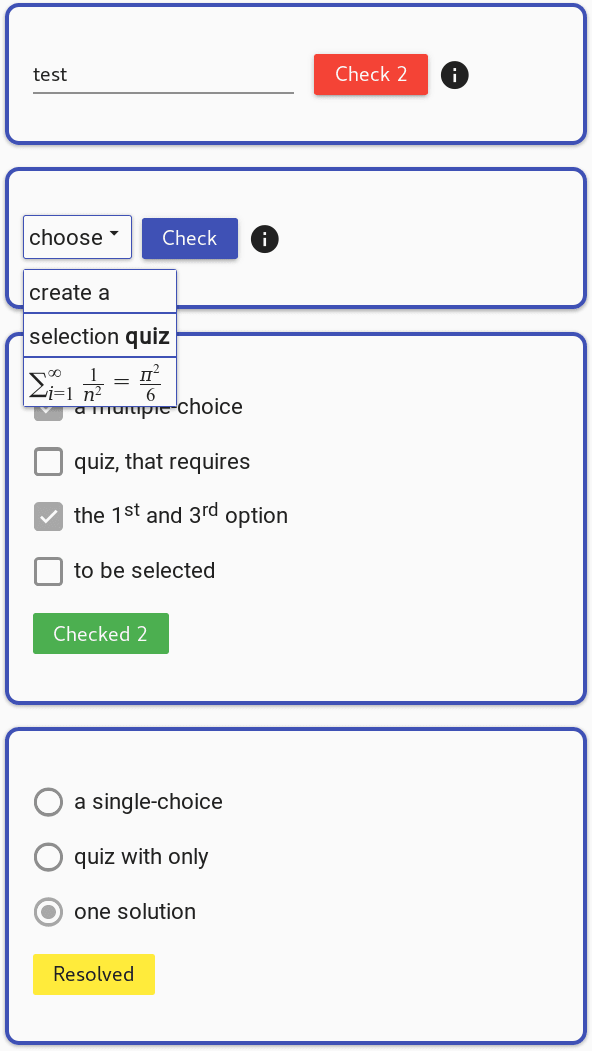

The support for quizzes is backed into the language (see line 58). Adding a new line with starting double brackets adds also a new option to the quiz. Singe-choice quizzes are defined similarly, but with parenthesis [(X)]. LiaScript has also support for [[text|select]] and generic-quizzes [[!]]. Hints [[?]] can be attached as well as more expressive solutions.

ASCII-art (line 63-74) gets translated into nicely rendered images. LiaScript has also support for effects and transitions, similar to PowerPoint, and native support for text2speech, which can be used to develop screen-cast like presentations, among with other features (see the documentation https://github.com/liaScript/docs). But above all, it is still Markdown that can be read/written without a technical background.

The most popular file-hosting platform for version control led projects with git: https://github.com ↩︎

2.2 LMS: Restricted Access to Educational Resources

As the name suggest, a LMS is more about managing educational resources, administration, controlling access, and reporting and tracking on user progress, than it is about creating new content. Additionally, various communication channels are provided between students and teachers, such as wikis, forums, and chats. The offered authoring tools are mostly WYSIWIG[1]-editors, but they also do have support for plugins or extensions that allow to create more sophisticated learning materials with quizzes, multimedia content, user repositories, etc. Indeed, this was only a brief overview on LMSs, for more detailed information see [Fa11].

What You See Is What You Get: An editor that displays content closely resembling the (printed) result. ↩︎

3 Methodology

We chose some of the most popular LMSs (i.e., Moodle, ILIAS, Canvas, Edmondo)[1] for the comparison with LiaScript, which is not trivial task, since LiaScript represents an entirely text-based approach, while the LMSs are based on GUIs. Nevertheless, both are used solve similar tasks: creating, adapting, and sharing educational content. We apply different metrics to identify quantitative differences. Qualitative measurements are probably possible, but require larger analysis, while the results remain highly speculative.

How many Lines Of Code (LOC) are required to print out “Hello World” on the console with a certain programming language? This is a simple metric to compare programming language simplicity and to measure boilerplate code. The example below, shows how this task is solved in Python, it requires one LOC and one command to execute it:

print("Hello World!") # command: python HelloWorld.py

With correct indentation, C++ requires 6 or at least 5 LOC in total to solve the same problem (see line 47 in Fig. 1). Two steps are needed to compile and execute the code. A more complex metric that is based on this principle is the Time To Hello World metric (TTHW) or in other words From Zero to Hero metric. It is often applied as a key determinant in programming languages and measures the time it takes for a novice programmer to write and execute the first HelloWorld program. But, this metric is also applied to measure the “usability” of an Application Program Interface (API) [An16]. An API is an abstract set of clearly defined methods, that control the access and configuration of certain functionalities, which are offered by a software module or library. Hence, there is little difference to a GUI, which is used for the same purpose, but on program-level. Thus, successful HelloWorld-states can also be quantified in GUI development, how long does it take to complete a task (time-on-task), number of clicks (also page-views), task level satisfaction (subjective measure on the difficulty of a task), next to others.

We provide an unconventional shortcut get to the LMS metrics, instead of performing various tests with different user groups [Bu08] or usability experts [MF15] we simply ask professionals. There are various tutorials on YouTube explaining how to set up a course in a certain environment. We analyzed the top ranked tutorials on integrating multimedia resources and quizzes for the chosen LMS. We measured their length (time-on-task) and counted the number of performed clicks and page-switches. If multiple solutions were presented in one video, then the average was stored. The number of comments with focus on difficulty (-1) or simplicity (+1) were summed up and associated with task-level-satisfaction.

Websites of the chosen LMSs: https://moodle.com, https://www.ilias.de, https://www.canvaslms.com, https://www.edmodo.com ↩︎

4 Comparison

We try to discuss several aspects and provide the measured metrics. All recorded data is stored for further review at the Open Science Framework (visit https://osf.io/3rweg). At the end the reader has to decide, which approach fits more for her/his purposes, based on personal preferences and skills.

4.1 What are the Requirements for Development?

All LMSs require a server installation with a login. Thus, working on a course mostly happens online and via the offered web-interface and with the required user permissions. Mostly in that case means, that there are some desktop-authoring systems (e.g. iSpring authoring Tool), which do have support for SCORM[1] and can be used to work offline. But, not all LMSs do have support for this standard, which makes it even a more a challenging task to get such content imported into the desired LMS. In contrast to this, a LiaScript course can be a simple git-repository[2] hosted/published on Github and developed locally. Everything that is required is a simple text editor. To ease the development process with the Atom editor, a snippets-plugin[3] is provided, next to the previewer, which provides a search on all language features and inserts fragments, it also provides more detailed information and examples.

Sharable Content Object Reference Model (col. of eLearing standards): https://adlnet.gov/research/scorm/ ↩︎

See the exemplary LiaScript course about LiaScript: https://github.com/andre-dietrich/e-Learning-2019 ↩︎

liascript-snippets: https://atom.io/packages/liascript-snippets ↩︎

4.2 How to add Multimedia Resources?

As depicted in the image below, the integration of audio and video-content is just an extension to the common Markdown syntax for links. A link can be given a name in brackets, which is followed by an absolute or relative URL in parentheses. A starting exclamation mark is used to indicate an image resource. That was the Markdown part so far. In LiaScript you can use a question mark to indicate audio resources (we hoped that this somehow resembles an ear) and by combining the image with the audio notation, it is possible insert video content. By doing this, the additional elements are still valid links in Markdown and any other Markdown-viewer, but in LiaScript this multimedia content gets displayed automatically within the appropriate web-player.

[link](url.html) |

link |

|

|

?[audio](url.mp3) |

|

!?[video](url.mp4) |

However, as the screen-casts reveal, integrating multimedia content to one of the LMSs seems to be a more challenging task and requires to deal with a couple of user interfaces. The overall average time-on-task was 3:06 minutes and required 11 clicks and 5 page changes.

Tab. 2: Average user-interface metrics for attaching movies to 4 LMSs (see https://osf.io/kb845)

| System | time-on-task | # of clicks | # of pages | satisfaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canvas | 02:56 | 10.4 | 5.1 | 0.83 |

| Edmodo | 02:33 | 9.1 | 2.9 | 0.00 |

| ILIAS | 02:59 | 11.2 | 5.3 | 0.00 |

| Moodle | 03:51 | 13.9 | 7.3 | 0.27 |

If content from other websites (e.g., YouTube, Vimeo, TeacherTube, Soundcloud, etc.) was imported, users had to work with HTML code. Thus, search for the embed-code on the content-site and import it by switching to code editing mode. Compare this, with the LiaScript notation. LiaScript also recognized links from the aforementioned sources. Hence, you only have to provide a link to the desired YouTube-site and the video will be embedded automatically. But, it has to be noted that a similar solution is offered by Canvas, which requires only 3 clicks and embeds the video view, only by pasting a YouTube-URL.

4.3 Where is all the Data?

For a LMS the case is clear, everything is stored on the server. The progress and state of each user is recorded, which enables sophisticated tracking and reporting, and thus provide useful information for course developers and teachers. LiaScript courses in contrast are freely accessible and store all states and the personal progress locally within the browser. A registration or login is not required, which might be considered as a first barrier by some users, before starting or simply trying a course. But, this local storing of personal data might also be considered as a drawback, because opening the same course on another device or even in another browser is like a new start.

4.4 How to add quizzes?

Of course, adding quizzes takes longer than including multimedia resources and is much more diverse. The overall mean time-on-task was 6:47 minutes, which required 36 clicks and 10 page changes on average. The task-level-satisfaction was also worse, there are two notable cases for Moodle: One person was speaking ironically about the “very intuitive way of creating course”, while another one used the phrase “Damn it”, after multiple attempts in creating the same course, due to some lost configuration settings.

Tab. 3: Average user-interface metrics for adding quizzes to 4 LMSs (see https://osf.io/kb845)

| System | time-on-task | # of clicks | # of pages | satisfaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canvas | 08:34 | 51.2 | 15.6 | 0.38 |

| Edmodo | 05:59 | 24.9 | 8.2 | -0.10 |

| ILIAS | 04:04 | 19.3 | 7.7 | 0.10 |

| Moodle | 08:33 | 47.5 | 9.9 | -0.92 |

Compare this with the creation of quizzes in LiaScript, as depicted below (or see lines 58 and 59 in Fig. 1). It requires only a little amount of boilerplate code to create different types of quizzes.

[[solution]]

[[ create a

| (selection **quiz**)

| $\sum_{i=1}^\infty\frac{1}{n^2} =\frac{\pi^2}{6}$

]]

[[X]] a multiple-choice

[[ ]] quiz, that requires

[[X]] the 1^st^ and 3^rd^ option

[[ ]] to be selected

[( )] a single-choice

[( )] quiz with only

[(X)] one solution

Of course, our way of creating quizzes can only be used for self-evaluation and not as in a LMS for assessment with points, penalties, max. number of retrials, shuffling, etc. In all systems it was therefor possible to define quiz-banks, which are used as a repositories and allow to display a subset of different quizzes to different users. LiaScript in contrast defines quizzes in a plain-text format, visible to all that know the “raw” course URL (see the next section).

4.5 Support for versioning and internationalization/localization?

To be short, we found no hints on versioning in LMSs. Although, there are different back-up strategies offered and SCORM could also be used as a format for versioning, it does not allow to host/run different versions of a course in parallel. It exists only one course in the most up-to-date version or different courses that represent different versions. Thus, internationalization/localization requires to repeat every change in every translated version of a course.

LiaScript does not support versioning by default, but by using git and publishing on GitHub, these features come for free. It is possible to refer to the most up-to-date version (1), use tags to define versions (2), or to open any uploaded version, since every update is labeled with an unique identifier (3).

- https://raw.githubusercontent.com/andre-dietrich/e-Learning-2019/master/README.md

- https://github.com/andre-dietrich/e-Learning-2019/blob/1.0.0/README.md

- https://github.com/andre-dietrich/e-Learning-2019/blob/434dd2188294296cf68bab49c97cb75582ee59d3/README.md

- https://github.com/andre-dietrich/e-Learning-2019/blob/german/README.md

Remember, LiaScript is only a text-file and to be complete, a Unicode text-file, which allows to create courses in any known language and to publish them in parallel, only by using git-branches (4).

4.6 Support for Extensions & Add-ons?

Extensions or Add-ons allow to develop courses with more interactive and thus eye-catching elements. Before they can be used, they need to be installed on the server-side, which affects the LMS user interface and requires enough user permissions. On the other it exists a standard for Learning Tools Interoperability (LTI), that allows to link content or apply services from so-called LTI provider to a LMS course, see [Se10]. This content is integrated via an iframe and authentication is handled in the background.

In contrast to this, every LiaScript course can define its own “extensions” as macros, as it was briefly introduced in Sec. 2.1. These macros can be shared among different courses, either by copy and pasting the source-code directly into the main-header of the LiaScript document or by using the following directive (also within the main-header):

import: https://raw-course-url.md

If a course is hosted on Github, it is possible to reference to any desired version, as it was highlighted within the previous section. All required macros, JavaScript libraries, CSS style-sheets, will automatically be loaded at the initialization. See also the template-index (https://github.com/liaTemplates), which provides a list of self-documenting macros, ranging from 360 degree imaging, computer algebra, visualization, up to online programming in various languages.

5 Discussion

LMSs are more about recording users and generating scores and reports to measure their progress. This becomes even more obvious, if you search for Add-ons and extensions for your LMS[1]. Only a minority is dealing with content and the integration of new interactive elements. Thus, even if someone is willing to create online courses this way, the majority of GUI elements with too many settings and required clicks and page switches seem to be more daunting than useful. Learning and understanding all of these concepts (and every plugin probably posses its own user logic) before being able to add some content, seems to be simply wrong. That is why we believe that LMS are not only used to restrict the access to educational resources, but also restrict their creation.

LiaScript was developed from an opposite perspective, by focusing on content first through the usage of a simple but yet extendable DSL. This allows to treat courses similar to open-source projects, which can be shared and developed accordingly even by larger developer groups. Since in teaching there is no single source of truth, there can also exist multiple versions of the same course. In open-source terminology that means: a teacher could simply “fork” an existing course and modify or translate it into another language and “push” the changes back or proceed with his own course. Due to discussions with students, the course can be continuously improved by “committing” new versions, while older ones are still accessible, or by creating “branches” for different groups of students. This might sound odd for a non-programmer, but makes totally sense for every programmer[2].

Additionally, even without an online interpreter, the LiaScript remains readable and editable as a text document. One of the key-challenges of LiaScript was to overcome this segregation of learning materials into textbooks, PowerPoint presentations, and videos. By using this DSL, the user can decide what is her/his favorite mode and switch between.

The Moodle plugin repository for instance includes 1584 contributions. The majority of the most popular plugins address themes and certificates, not content: https://moodle.org/plugins/stats.php ↩︎

Git Terms Explained: https://linuxacademy.com/blog/linux/git-terms-explained/ ↩︎

Bibliography

[Ca14] Cavus, N., Zabadi, T.: A Comparison Of Open Source Learning Management Systems. In Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 143, pp. 521-526, 2014.

[Le05] Lewis, Barbara A., et al.: Learning management systems comparison. In Proceedings of the 2005 Informing Science and IT Education Joint Conference, pp 17-29, 2005.

[Ma08] Martin, L., et al.: Usability in e-Learning Platforms: heuristics comparison between Moodle, Sakai and dotLRN. In Proceedings of the sixth International Conference on Community based environments, pp. 75-84, 2008.

[Di19] Dietrich, A.: LiaScript: A Domain-Specific-Language for Interactive Online Courses. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on e-Learning, (accepted), 2019.

[MD19] Markdown, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Markdown, accessed 09/03/2019.

[An16] Andrew, M. et.al: API Usability at Scale. In 27th Annual Workshop of the Psychology of ProgrammingInterest Group-PPIG, pp. 177–187, 2016

[Fa11] Boneu, J.-M.: Survey on Learning Content Management Systems. In (Ferrer, N., Alfonso, J., ed.): Content Management for E-Learning, Springer, pp. 113-130, 2011.

[Bu08] Buzzetto-More, N.: Student Perceptions of Various E-Learning Components, In (Koohang, A.): Interdisciplinary Journal of E-Learning and Learning Objects, Volume 4, 2008.

[MF15] Medina-Flores, R.; Morales-Gamboa, R.: Usability Evaluation by Experts of a Learning Management System. In IEEE Revista Iberoamericana de Tecnologias del Aprendizaje, Volume 10, pp. 197-203, 2015.

[Se10] Severance, C. et.al: IMS Learning Tools Interoperability: Enabling a Mash-up Approach to Teaching and Learning Tools. Technology, Instruction, Cognition and Learning, 7(3-4), pp. 245-262, 2010.